Truth Is Pictures - How We See What's Real

Have you ever stopped to think about what "truth" really means? It's not always the same as a cold, hard fact. For instance, saying "chocolate is good" feels true to many, yet it is not a scientific fact. Or, when someone says "I love my mom," that's a deep, personal truth, though it cannot be measured or proven in a lab. Even something like "God exists" is a truth for countless people, built on belief and personal experience, not something you can just verify with a simple check. So, it's almost as if what we consider true often comes down to how we personally experience or view things, rather than some universally fixed reality.

Many things exist in what we call "truth" because of how an observer sees them, and not necessarily as a hard, objective fact. This way of looking at things suggests that our personal viewpoint shapes what we accept as real. It's a bit like looking at a painting; what one person sees and feels might be quite different from what another person experiences, and both are true for them. This idea, where truth is less about an independent reality and more about how we interact with it, is pretty interesting, wouldn't you say?

This way of thinking about truth, where it feels more like a collection of personal perceptions, helps us understand why people can hold different beliefs yet all feel they are right. It means we might need to look beyond simple definitions and explore how our own thoughts and observations play a big part in building what we call "true." We'll take a closer look at this fascinating idea, figuring out how our individual perspectives truly create the pictures of truth we carry with us.

Table of Contents

- What Makes Something True for Us?

- Is Truth Just a Collection of Ideas?

- Can Truth Change with Who's Looking?

- The Difference Between What's Real and What We Believe

- Why Some "Truths" Don't Always Work Out?

- What Does It Mean for Something to Be "Truth-Apt"?

- Is Truth Always a Cause, Never an Effect?

- Beyond Simple Accuracy - What Else Is Truth?

What Makes Something True for Us?

When we talk about truth, it's often more personal than we think. Consider the idea that "chocolate is good." For a person who enjoys the taste, this statement holds a deep truth. Yet, for someone who dislikes chocolate, it's simply not true. This isn't about facts that can be checked by everyone, like the melting point of ice. Instead, it's about a feeling, a preference, a way of experiencing the world. Similarly, when someone declares, "I love my mom," that's a truth born from emotion and connection. You can't really prove it with evidence, but its authenticity is undeniable to the person saying it. And, for people who believe "God exists," this is a profound truth that shapes their entire outlook on life, even though it rests on faith rather than empirical proof. So, what we find to be true can often depend on our inner landscape, our feelings, and our personal experiences, wouldn't you say?

When Our Personal View Shapes the Truth Is Pictures

A lot of things exist as "truth" because of the way an individual person observes them, rather than being something that is a hard, cold fact for everyone. This way of looking at things suggests that our personal viewpoint really shapes what we accept as being real. It's a bit like how different artists might paint the same scene, each creating a unique interpretation. Each painting, in its own way, captures a certain "truth" of that scene, but none of them are the single, complete, objective fact of it. This idea, where truth is less about some independent reality and more about how we interact with it, is quite interesting, isn't it? It suggests that our personal experiences and perspectives are the lenses through which we construct our individual pictures of truth.

Is Truth Just a Collection of Ideas?

There's a way of looking at truth, sometimes called "deflationism," that really isn't a theory of truth in the way we usually think about it. It's more like a different approach to the whole idea. Instead of seeing truth as some deep, mysterious quality that statements have, this perspective suggests that when we say something is "true," we're just doing something with language. For example, saying "It is true that the sky is blue" is pretty much the same as just saying "The sky is blue." The word "true" doesn't add much beyond confirming the statement. It's like a linguistic placeholder, a way to agree or emphasize, rather than pointing to some hidden property of reality. This view suggests that truth and falsehood can be thought of as two big collections of judgments we make. Truth, in this sense, is made up of those judgments that stick together logically, staying consistent without needing outside proof. It's a way of organizing our thoughts and statements so they don't contradict each other, which is pretty neat when you think about it.

How Our Thoughts Create a Truth Is Pictures

So, in this way of thinking, what we call truth depends a lot on the person who is putting that truth together. Consider Newton's laws of motion, or even the basic principle that something cannot be both true and false at the same time. These ideas, or any truth for that matter, are only "true" as long as people, or "dasein" as some thinkers might say, exist to think about them and give them meaning. If there were no minds to observe, to categorize, to make sense of the world, would these truths still hold? It's a question that makes you pause, isn't it? This suggests that our very existence, our capacity to think and observe, is a fundamental part of how these pictures of truth come into being. Without us, they might not have a place to exist.

Can Truth Change with Who's Looking?

It's interesting to consider how all relative truth might be seen as a way of getting closer to one single, absolute truth, but through many different individual truths. Think about it: what seems true to one person in their specific situation might be a slightly different version of what's true for another. Yet, perhaps all these individual perspectives are like pieces of a larger puzzle, each contributing to a more complete, ultimate picture. This suggests that while our personal truths are valid for us, they might also be steps on a path toward something bigger, something universally true. It's a way of seeing how our individual perceptions, while distinct, could also be connected to a more general reality, which is quite a thought.

The Observer's Hand in the Truth Is Pictures

Truth, in a lot of ways, is something we take for granted. It's assumed, almost like the air we breathe. The very way we make assumptions, as shown through what some call the "trillema" – the idea that any claim needs either an infinite regress of justifications, a circular argument, or an arbitrary starting point – shows how deeply assumption is woven into our search for truth. We start somewhere, often with something we simply accept as given. This means that the observer, the person doing the assuming, has a very direct hand in shaping what they consider to be true. Their initial points of acceptance or belief become the foundation for the pictures of truth they build for themselves. It's a powerful idea, that our starting points so deeply influence where we end up with our understanding.

The Difference Between What's Real and What We Believe

There's a common understanding that there's a clear difference between a fact and an opinion. Physical facts, for example, are things you can check and prove, like the fact that water boils at a certain temperature at sea level. These are things that can be verified by anyone, regardless of their personal feelings. An opinion, on the other hand, is something that varies from person to person and might be based on personal beliefs, feelings, or even faith. Saying "blue is the best color" is an opinion; it's not something you can prove. So, while facts are generally seen as objective and verifiable, opinions are subjective and personal. This distinction helps us sort out what's universally agreed upon from what's a matter of individual perspective, which is pretty helpful in conversations.

Sorting Out Fact from the Truth Is Pictures

Truth and falsity are like labels or values that we give to statements, or what thinkers call "propositions." Once we decide if a statement is true or false, those values can actually affect the truth or falsity of other statements. It's a bit like a chain reaction. If you accept one statement as true, it might make another related statement also true, or perhaps even false. However, the more general or broad a concept becomes, the harder it is to pin down its truth value. Think about big ideas like "justice" or "beauty." It becomes much more difficult to assign a simple true or false label to them because they mean different things to different people and in different situations. This shows how complex the process of sorting out our pictures of truth can become when we move beyond simple, concrete statements.

Why Some "Truths" Don't Always Work Out?

Consider the moral idea that "it is a duty to tell the truth." If we were to take this idea absolutely, without any exceptions, and always follow it no matter what, it would probably make living in any kind of society impossible. Imagine a world where everyone always, without fail, said exactly what they thought, even if it was hurtful, inappropriate, or revealed sensitive information that could cause harm. We have pretty direct proof of this in everyday life. Sometimes, a small white lie or a moment of discretion is necessary to maintain peace, protect feelings, or ensure safety. This suggests that while telling the truth is generally a good principle, it's not an unconditional rule that works in every single situation. The practical demands of living together often mean we need to consider more than just the raw truth, which is a bit of a balancing act.

The Limits of Our Shared Truth Is Pictures

A "truth value" is like a quality that a statement, or a "piece of knowledge," possesses. It describes how that statement connects with what's real. If a statement is true, it accurately describes reality. If it's false, it doesn't. For example, the statement "The cat is on the mat" has a truth value. If the cat is indeed on the mat, the statement is true. If the cat is sleeping in a basket, the statement is false. A false statement simply doesn't match up with how things are in the world. This way of thinking helps us evaluate individual bits of information and see if they line up with our observations of reality, shaping the shared pictures of truth we create together.

What Does It Mean for Something to Be "Truth-Apt"?

A sentence is considered "truth-apt" if, in some situation, when it's spoken with its usual meaning, it could express a statement that is either true or false. This means the sentence has the potential to be evaluated for its truthfulness. For example, the sentence "The sky is green" is truth-apt because, even though it's false in our world, it could theoretically be true in another context, or it clearly expresses a false idea about our world. However, a sentence like "Ouch!" or "Hello" isn't truth-apt because it doesn't express a statement that can be judged as true or false; it's an exclamation or a greeting. So, to argue anymore over whether a particular sentence can be true or false, we first need to check if it's even the kind of sentence that can hold a truth value at all. This helps us focus our discussions on statements that actually have a claim to describing reality, which is quite useful.

The Framework for Our Truth Is Pictures

When we talk about truth, it seems that "accuracy" is often thought of as being the same thing as truth in the study of knowledge, though it's not always clear if that's entirely correct. Accuracy means being precise, free from errors, and correct in every detail. If a map is accurate, it perfectly reflects the terrain. But is that the same as being true? Perhaps truth is something broader, something that encompasses accuracy but also includes other aspects, like meaning or relevance. For example, a caricature might not be "accurate" in every detail, but it can still convey a deeper "truth" about a person. So, the definition of truth might not just be about being perfectly accurate. It might also involve how something resonates with our experience or understanding, adding layers to the pictures of truth we hold.

Is Truth Always a Cause, Never an Effect?

One interesting idea about truth is that it must be the source or the origin of something, but never just an outcome or a result. In other words, truth is something that leads to other things, rather than being something that is produced by them. A regular person might say that truth simply has certain qualities, like being dependable or foundational. It's not something that just happens; it's something that is fundamental. It's like saying that the sun is the source of light, not an effect of light. So, truth itself is something that is connected to being a starting point, a primary element. It's about what brings things into being or gives them their validity, rather than being something that is merely brought about. This perspective really shifts how we think about where truth comes from.

The Origin of a Truth Is Pictures

Thinking about the origin of truth also brings up questions about what makes truths true. Theories of truth often explore things like, "What is the relationship between statements that are true and the actual things or situations that make them true?" This is not to be confused with simply asking what truth is in itself, but rather how it connects to the world around us. For instance, is a statement true because it corresponds perfectly to a fact in reality? Or is it true because it fits consistently within a system of other beliefs? These questions help us understand the very foundations upon which our pictures of truth are built, probing into the deeper connections between our ideas and the world we live in.

Beyond Simple Accuracy - What Else Is Truth?

Truth and falsity are like values that we give to statements, or what thinkers call "propositions." These values, once we figure them out, can actually have an impact on the truth values of other statements. It's a bit like a network where one confirmed truth can influence how we see related ideas. For example, if we establish that "All birds have feathers" is true, and "A robin is a bird" is true, then it logically follows that "A robin has feathers" must also be true. However, the more general a concept becomes, the harder it is to pin down its truth value. Think about very broad ideas, like "happiness" or "justice." It becomes much more difficult to assign a simple true or false label to them because they mean different things to different people and in different situations. This shows how complex the process of determining truth can become when we move beyond simple, concrete statements, reflecting the many shades in our pictures of truth.

A Broader View of the Truth Is Pictures

When we look at the idea of truth, it's clear that it goes beyond just being accurate. It involves how we personally see things, how our thoughts fit together, and how our existence shapes what we consider real. We've seen that truth can be a personal feeling, a consistent set of ideas, or even something that depends on who is observing it. It's not always a hard fact, and sometimes, even a widely accepted moral truth needs to be flexible in real-world situations. Ultimately, understanding truth means looking at how statements connect to reality, how they originate, and how our own assumptions play a role. It's about recognizing that what we call "truth" is often a rich, layered collection of perspectives, much like a series of unique pictures.

September 30 - National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

107393633-1711553838607-gettyimages-2111708727-truthsocial-3.jpeg?v

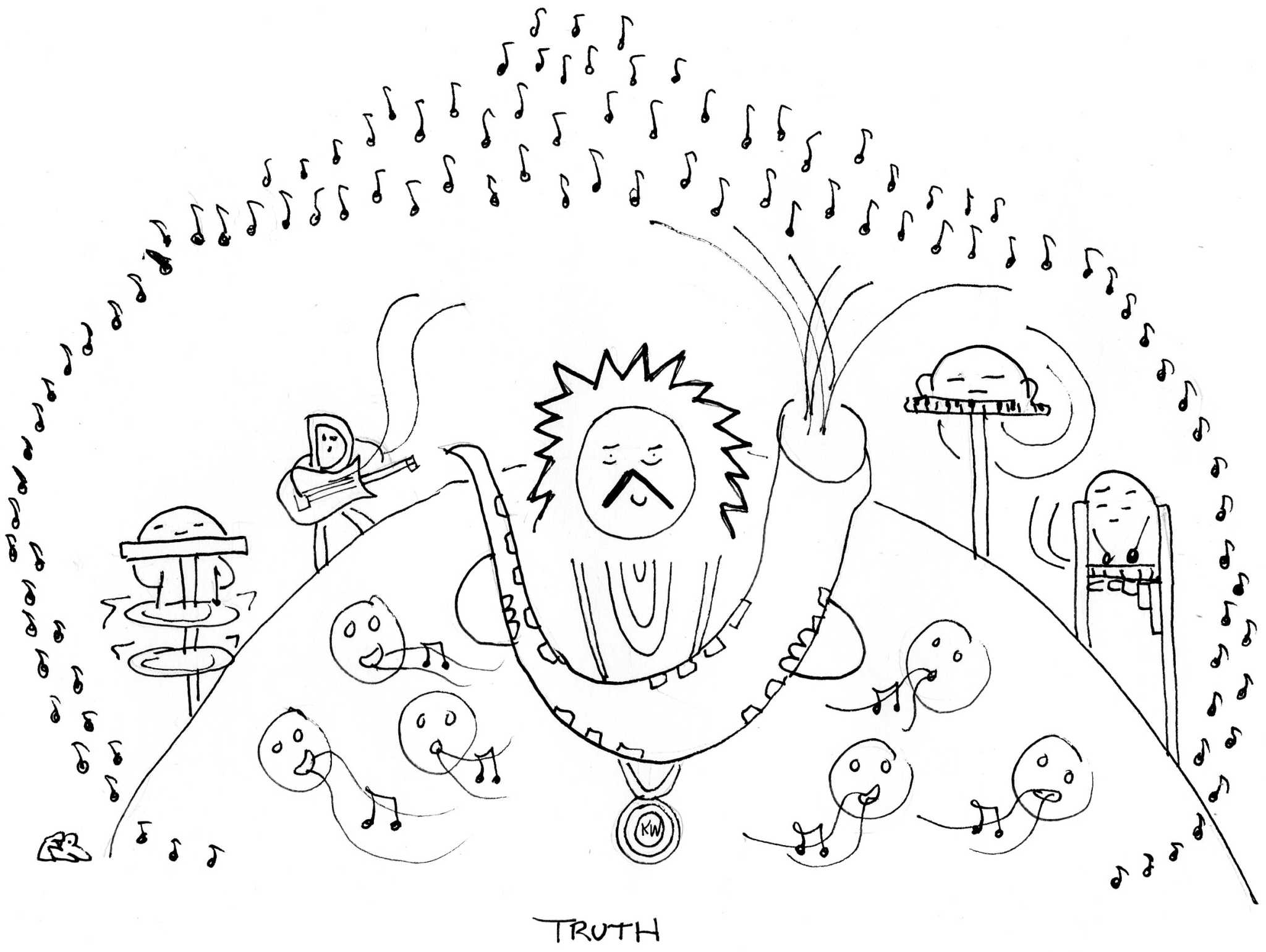

Truth | Song Cartoons